Director’s Statement

Claudia Pryor Malis

It is January, 2006. I’m standing in front of Miss York’s 5th period biology class in Westinghouse High School in an all‐black section of Pittsburgh, PA. About twenty young, hostile, African‐American faces are staring back at me. Despite my black skin and salt and pepper dreadlocks, privilege sticks out all over me. I’ve come to their school, in their neighborhood, to ask them to help me make a documentary film about why HIV rates are higher among black people than any other group in America.

It is January, 2006. I’m standing in front of Miss York’s 5th period biology class in Westinghouse High School in an all‐black section of Pittsburgh, PA. About twenty young, hostile, African‐American faces are staring back at me. Despite my black skin and salt and pepper dreadlocks, privilege sticks out all over me. I’ve come to their school, in their neighborhood, to ask them to help me make a documentary film about why HIV rates are higher among black people than any other group in America.

They are not having it. Voices are raised. You are just here because we’re black! Westinghouse is not the school with AIDS! You’re no different than that newspaper reporter that made us look bad ‐‐ like we all have HIV, just  because we had an HIV awareness day. We’re not going to fall for that again! The teacher looks worried. She tries to get the students to calm down and listen to what I have to say, but the voices get louder and louder. I can’t compete.

because we had an HIV awareness day. We’re not going to fall for that again! The teacher looks worried. She tries to get the students to calm down and listen to what I have to say, but the voices get louder and louder. I can’t compete.

So I wait; letting their comments wash over me. In their eyes, there is distrust, anger, and worst of all, resignation ‐‐ that they have already been written off, thrown away by the world of whiteness and the world of middle class blackness. There is one girl who looks far too young to be in this class of juniors and seniors. She is the only student who hasn’t spoken a word. I look into her eyes hoping for a life raft. She doesn’t offer one. She just watches me intently. (She would later become the film’s production assistant and narrator).

But in that moment, I realize that my proper, “isn’t this a great opportunity” approach isn’t going to work. I abandon it. At the first lull in the yelling, I look the loudest student in the eye and firmly proclaim, “Yeah, I’m here because this is a black school. This is now a black disease. So where else would I be”?

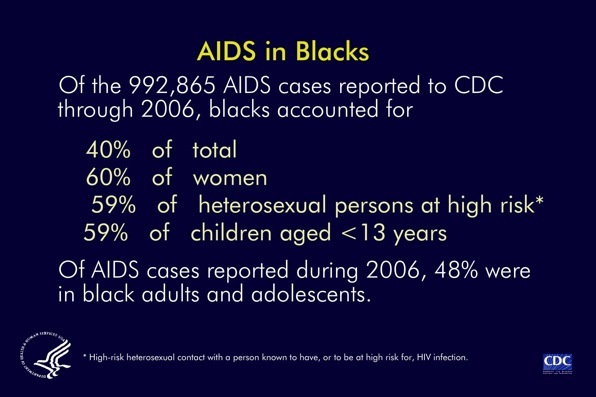

Dead silence. Black Americans are about 13% of the US population but, in 2006, we accounted for 45% of all the new HIV infections in the country, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

Dead silence. Black Americans are about 13% of the US population but, in 2006, we accounted for 45% of all the new HIV infections in the country, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

HIV is a seasoned and happy traveler through many of the realities associated with being black. It feeds off our poverty, our forced displacement, our disproportionate imprisonment, and our well‐earned distrust of the health care system.

It multiplies exponentially in our shame, our secrecy, and our religious fundamentalism. It may even be, according to one long‐term scientific study, a by‐product of our African ancestry.

HIV is also the latest stigma grafted on to a people desperately weary of being stigmatized. That’s what set off the waves of hostility from the students. There’s a choice facing us in black America right now: turn away from this new stigma or face it, unpack it, and remove its sting ‐‐ passive self‐destruction or active self‐love. Suddenly, there’s a loud buzz. Class is over; conversations end. Most of the students brush by me, eyes averted. But a few look at me with a mixture of wariness and appreciation. After all, this could fulfill their senior project requirement.

HIV is also the latest stigma grafted on to a people desperately weary of being stigmatized. That’s what set off the waves of hostility from the students. There’s a choice facing us in black America right now: turn away from this new stigma or face it, unpack it, and remove its sting ‐‐ passive self‐destruction or active self‐love. Suddenly, there’s a loud buzz. Class is over; conversations end. Most of the students brush by me, eyes averted. But a few look at me with a mixture of wariness and appreciation. After all, this could fulfill their senior project requirement.

And, ultimately, I learn that it only takes a few.